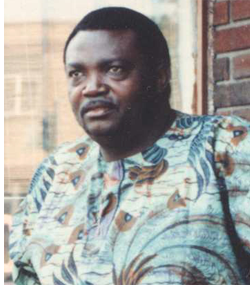

Franco Franco

1939 - 1989

"Il est mort," say French speakers when someone dies. In the fall of 1989 they said it about another great figure in Zaïrean music, the leader of O.K. Jazz, Luambo Makiadi, "Franco." He of rounded frame and booming voice, of flashing fingers against strings of steel, vigorous, robust, the picture of life died in Brussels at the age of fifty-one.

He was called "the grand master," and it was true. One of the pioneers of modern Congo music, he recorded more than 100 albums and an uncountable number of singles. His ability to capture listeners—with words for those who understood Lingala or French and with an uncanny musical sensibility for those who didn't—coupled with a healthy dose of business acumen, fashioned and sustained the seemingly perpetual music machine that was O.K. Jazz.

But Franco's three decades atop the world of African music came to a sad and stunning halt. The good life that fueled his rapidly expanding girth took its toll. In the last year of his life his weight plummeted. He failed to show up in March 1989 for a much-heralded reunion with his former singer Sam Mangwana at London's Hammersmith Palais, and he missed the band's American tour that summer.

The truth of his illness is hard to come by. Close associates, band manager Nsala Manzenza and artistic director Dizzy Mandjeku, claimed he suffered from kidney and stomach ailments. Rumors said he had AIDS. In an interview for Africa International quoted in the Paris newspaper Libération, Franco denied them: "You know in Zaïre, as soon as you're sick everyone yells AIDS. Whether it is cancer, malaria or dysentery, the rumors fly. 'Hey, did you see so-and-so, did you see how skinny he's gotten? Oh, it's AIDS.' Whereas you could have another disease that's just as dangerous. As for me, I don't have AIDS. It's true that I've gotten a lot thinner and that I now weigh less than 100 kilos [about 220 pounds] whereas I have weighed up to 130 kilos [290 pounds], but the doctors have told me I have a kidney disease. I'm taking care of myself accordingly, and things are going well."

Life's precariousness was hardly a matter for concern back in 1956 when Franco was something of a prodigy at the Léopoldville recording house of Loningisa. He was eighteen years old and part of a large stable of musicians that included some of the pioneers of modern Congolese music—Henri Bowane, Paul "Dewayon" Ebengo, Dessoin Bosuma, and Vicky Longomba, all from the Belgian Congo, and Lando Rossignol, Daniel "De La Lune" Lubelo, and Jean Serge Essous from across the river in Congo Brazzaville.

For several years, since around 1953, the Loningisa ensemble had been cranking out records and a tidy profit for the studio's owner, a foreign businessman named Papadimitriou. But in 1956, six of the studio's musicians got hired to play at the O.K. Bar in Léopoldville, and O.K. Jazz was born. On one of their first records, "On Entre O.K. On Sort K.O." (one enters OK, one leaves KO'd knocked out), made in late 1956, the band introduces itself. There is Franco on guitar, Dessoin playing hand drums, De La Lune on bass, clarinetist Essous, and singers Vicky and Rossignol. On the strength of his musicianship and personality Franco emerged as the star.

"Not a pretty boy," wrote journalist Jean-Jacques Kande in 1957, describing the Congo's newest heartthrob. "Slightly taller than the average. Eyes the color of fire, sometimes laughing, sometimes dreaming. Hair cut any which way giving his appearance a very combative air. Very dark black skin. Thus appears the current number one guitarist of the town of Léopoldville, the electric guitarist who makes the hearts of women spin. For them, his name is Franco, from his real name François Luambo. He wears plaid shirts and narrow pants cut cowboy style."

Relying heavily on traditional folk elements for inspiration, the members of O.K. Jazz refined and adapted them to fit the capabilities of Western instruments and recording technology. Building on African rhythms and those like the son repatriated from Latin America, they translated into song the cares and concerns of the young, rapidly rising Congolese urban class. As Kande, echoing the thoughts of many of his countrymen, put it, passionate love songs like "Elo Mama" and "Naboyi Yo Te," "take you by the throat, twist your heart, electrify you."

Where Joseph Kabasele's African Jazz was developing the multifarious guitar sound of Nico, Dechaud, and Tino Baroza, O.K. Jazz blended a single guitar with a saxophone. Isaac Musekiwa a saxophonist from Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) joined the band in 1957 following a stint with Kabasele's African Jazz. "I was playing the first part," he says, "and Franco was playing the second part on guitar. Guitar and sax." Some time in 1958, Angolan guitarist Antoine "Brazzos" Armando was added, and O.K. Jazz began to refine its own strain of guitar interplay.

Politics—independence and the Congolese civil war—heavily influenced the band's evolution by forcing personnel changes and providing rich material for new songs. "Lumumba Héros National" praised the country's new prime minister in 1960, and "Liwa Ya Lumumba" mourned his assassination a year later. Diplomatic flare-ups periodically drove the Brazzaville musicians back across the river and opened spots for new talent. O.K. Jazz became a virtual music school accepting, training, or introducing dozens of artists over the years. Sam Mangwana, Wuta Mayi, Antoine "Papa Noël" Nedule, Michel Boybanda, Jean "Kwamy" Mossi, Kiamuangana "Verckys" Mateta, Joseph "Mujos" Mulamba, and Ntesa "Dalienst" Zitani are only a few of the stars that have played with Franco.

Playing with O.K. Jazz was akin to earning a degree. "It's something to be very proud of, because it has such a history," said Mandjeku shortly before Franco's death. To join the band was "not difficult," he explained. "First of all you must know the work, and second there must be a place open." Most aspirants had to undergo an audition. Either they were asked to perform their own compositions or they played O.K. Jazz standards with members of the band. Established musicians simply made it known that they wanted to join and were picked up when a slot became available.

Gerry Dialungana's entrance into O.K. Jazz was fairly typical. Born only five years before the band was formed, he grew up admiring the singing voice of Rochereau and teaching himself guitar by mimicking Docteur Nico. "I didn't choose to be a musician," he says, "it just happened." He began playing with neighborhood groups and in 1970 made his professional debut with Les Malous. In 1973 he joined Dalienst in Les Grand Maquisards and three years later graduated to O.K. Jazz where he became a leader in the band's directional committee.

O.K. Jazz was formally organized with Franco as president and a directional committee composed of band members who took responsibility for discipline, rehearsal schedules, equipment, social functions, and general operations. If O.K. Jazz is to continue in existence, it will probably be under the leadership of Franco's vice-president, guitarist Simaro Lutumba.

With such an array of talent, there was never a shortage of material to record. Franco himself was a prolific composer who, according to Mandjeku, liked to get together with a singer to work out a song idea. He would then call in a bass player or another instrumentalist to help complete the composition. If another musician had a song, it would be put on a schedule, and he would audition it for the group. Many songs started as mere skeletons and were developed as collaborative efforts in rehearsal.

"Tradition is a great influence in my music," Franco told Jon Pareles of The New York Times in 1983. "In my music I put all my soul, all my spirit, and my soul is a traditional one, because I was born in a family that respected tradition. My mother was always singing traditional songs. The traditional music lacks some sounds, while the modern music has the guitars and the saxophones and many other things. But the spirit of the music is the same."

Despite his close connections to the government of Zaïre's President Mobutu—he recorded several songs in support of Mobutu's policies including "Candidat Na Biso Mobutu" (Mobutu is our candidate)—Franco developed a reputation as a spokesman for the people. "Lopango ya Bana na Ngai" (the land of my children) spoke against government land expropriations; "Ngai Marie Nzoto Ebeba" sings in support of Marie, a Kinshasa prostitute faced with the anger of her clients' wives; "Tailleur" was widely interpreted as a satire on a Zaïrean prime minister; "Attention na SIDA" warned against the scourge of AIDS. In 1979, Franco and his entire band spent two months in jail for what was ostensibly the offense of performing songs that were deemed by the authorities to be obscene, but at least some observers believed it to be punishment for stretching the boundaries of public criticism of Zaïre's ruling class.

Unlike most of his contemporaries who concentrated mainly on their art, Franco set out to insure that he and his troops would benefit monetarily from their creations. In the early sixties he established his own publishing house called Epanza Makita to issue records and try to collect royalties. Starting in 1961, he often recorded in Europe for Pathé Marconi and Fonior, and when Fonior folded, he established his own labels, Edipop, Visa 80, and Choc Choc Choc. He owned Mazadis, a small two-track recording studio in Kinshasa, for many years, and was a partner in Zaïre's only record pressing plant (both the result of the government's nationalization of foreign-owned businesses in 1974). He even had his own nightclub, the Un-Deux-Trois, where the band would play whenever it came to Kinshasa.

Bravado born of success prompted addition of the initials T.P.—for tout puissant, all powerful—to the familiar O.K. in the early seventies. A decade later the band had grown to become a massive entourage of more than forty people. They were often in such demand that they split into two units to satisfy their commitments.

Music promoter Ibrahim Bah of Washington, D.C.'s African Music Gallery recalls his 1983 experience of bringing the band to the United States for the first time: "I spoke with Franco several times and we had agreed we were going to have twenty-five people in the group...and I applied for the visas and got the visas. A week or so later he got pressure from his quarters that some people must be in the band, and he called me and said, 'Look Ibrahim, I can not come with just twenty-five, I've got to come with forty-five people.' I said, 'You mean forty-five—four, five?' He said, 'Yes, forty-five.'...He gave me the additional names and I applied [for visas] for the rest of their names. And immigration said, 'Hey, one moment this group is twenty-five, the next minute they're forty-five; what kind of group is this?'" Eventually additional visas were issued and the tour went ahead despite increased problems of logistics.

The band's songs seemed to lengthen in proportion to its size, although longer songs were actually a result of improved recording technology, changing formats, and the general trend in pop music around the world. The taut two or three minute gambols of the early days (dictated by the limits of technology) gave way to extended, laid back ramblings like "Très Impoli" and "Mario." In live performance the band supercharged its hits into torrid, up-tempo dance-floor grooves worthy of anything produced by the Paris soukous session bands. Fronted by Franco and singers Madilu System and Josky Kiambukuta with support from the sparkling guitars of Simaro Lutumba, Dizzy Mandjeku, Gerry Dialungana, and Thierry Mantuika, T.P.O.K. Jazz was a powerful outfit until Franco's death.

Despite his illness Franco recorded two albums with Sam Mangwana in early 1989, Franco Joue Avec Sam Mangwana and the wishful, ironic For Ever, featuring the track "Toujours O.K." But as his stamina slipped away, work became nearly impossible. He managed to appear at a final date with the band in Amsterdam only three weeks before his death, but he couldn't play. A British music publication, Tradewind, described his visit to London just before the Amsterdam show: "The once robust musician had lost a massive amount of weight and conducted interviews lying on his hotel bed. His comments were brief and often bitter, particularly over what he saw as a lack of European interest in African music. Franco seemed upset that no Western artists had seemed interested in working with him."

When death came October 12, President Mobutu declared a period of national mourning in Zaïre, and Franco's body was flown home for burial. For the remaining members of T.P.O.K. Jazz, it was a time of sorrow and uncertainty. "From '78 Franco has prepared his band to play without him," Manzenza said, in August of 1989, trying to be reassuring about the group's future. "It is an institution," said Mandjeku pointing to the band's success and longevity. But until that point T.P.O.K. Jazz had never been without Franco.

© 1989 Gary Stewart

This article first appeared in The Beat, vol. 8 no. 6, 1989. It later became a chapter in Breakout: Profiles in African Rhythm. I have updated it slightly based on my research for Rumba on the River.

|