Coda: For Dechaud, 7 December 1993

I didn't forget the request Dechaud made of me during our interview [18 June 1993]. I had promised to send him a guitar, so upon returning home to Washington, D.C., I set out to make good on my word. I purchased a nice Yamaha acoustic and took it to my friend Leo Sarkisian at the Voice of America. Leo arranged to have it shipped to Kinshasa through diplomatic channels, and the staff at the U.S. embassy took it from there. The following account first appeared in The Beat, vol. 13, no. 2, 1994.

Two men, separated by geography and nationality but united by their common humanity and love of music, stilled for a brief December moment the swirl of political chaos and economic desperation that soils the happiness of daily life in Zaire. Their lives had only touched each other in muted broadcasting studios of Washington, D.C., where the stylus of a Voice of America turntable met the black vinyl grooves of Congo music. There and in the pages of The Beat [vol. 12, no. 6, 1993] where the great guitar accompanist of African Jazz told a visiting journalist he didn’t even have a guitar to play anymore.

Still physically miles apart, the Voice of America’s “music man for Africa,” Leo Sarkisian, and Mwamba Dechaud, the guitarist “who made Lucifer and his 500,000 devils dance,” met in spirit in Kinshasa’s Centre Culturel Americain when a shiny, sleek acoustic guitar was presented to the guitarless musician.

Sarkisian, whose exquisite programs of African music and culture have graced the international airwaves for nearly 30 years, arranged for the new guitar to be shipped to Kinshasa through diplomatic channels. His colleague, Mary Carlin Yates, director of the American Cultural Center, together with the Zairean musicians union president, Moniania ma Muluma, better known as Roitelet, organized the ceremony which brought together the remnants of Kinshasa’s music establishment, Zairean television, and the local press to honor the great Dechaud.

“Humor, joie de vivre, love of pleasing the public, Mwamba Charles Dechaud is all of this at once when he picks up his guitar,” said Chargé d’Affaires, John M. Yates, currently the highest ranking American diplomat in Zaire, who made the official presentation. “He has produced," Yates continued, "a fabulous collection of 150 Zairean songs that Zairean men and women continue to dance to today.” One of them, “Africa Mokili Mobimba” (Africa and the whole world), is perhaps the best-known song ever to come out of the continent. Had Dechaud received his just rewards from this one song alone, he would be a wealthy man. But what the music business gives with the hand of adulation and celebrity, it crushes with the boot of corruption and deceit. Too many musicians have recorded Dechaud’s work but credited themselves or others to avoid making royalty payments. What money is legitimately paid vanishes in the sordid dealings among the bureaucracies that collect such fees. Dechaud and many of the older Zairean musicians receive virtually nothing for their creations, many of which, like “Africa Mokili Mobimba,” sell almost as briskly today as they did thirty years ago. “Humor, joie de vivre, love of pleasing the public, Mwamba Charles Dechaud is all of this at once when he picks up his guitar,” said Chargé d’Affaires, John M. Yates, currently the highest ranking American diplomat in Zaire, who made the official presentation. “He has produced," Yates continued, "a fabulous collection of 150 Zairean songs that Zairean men and women continue to dance to today.” One of them, “Africa Mokili Mobimba” (Africa and the whole world), is perhaps the best-known song ever to come out of the continent. Had Dechaud received his just rewards from this one song alone, he would be a wealthy man. But what the music business gives with the hand of adulation and celebrity, it crushes with the boot of corruption and deceit. Too many musicians have recorded Dechaud’s work but credited themselves or others to avoid making royalty payments. What money is legitimately paid vanishes in the sordid dealings among the bureaucracies that collect such fees. Dechaud and many of the older Zairean musicians receive virtually nothing for their creations, many of which, like “Africa Mokili Mobimba,” sell almost as briskly today as they did thirty years ago.

For Dechaud, the Voice of America guitar award marked the beginning of his fifth decade in the music business. He started as a teenager in the early 1950s singing with the celebrated guitarist, Jhimmy. He moved on to join with his brother, solo guitarist Docteur Nico, and singer Joseph Kabasele to form the group African Jazz where he developed his reputation as a splendid rhythm guitarist. Dechaud and Nico created African Fiesta Sukisa in the mid-sixties and played together until Nico’s death in 1985. For Dechaud, the Voice of America guitar award marked the beginning of his fifth decade in the music business. He started as a teenager in the early 1950s singing with the celebrated guitarist, Jhimmy. He moved on to join with his brother, solo guitarist Docteur Nico, and singer Joseph Kabasele to form the group African Jazz where he developed his reputation as a splendid rhythm guitarist. Dechaud and Nico created African Fiesta Sukisa in the mid-sixties and played together until Nico’s death in 1985.

Dechaud keeps active today playing with a group of old-timers called Afric’Ambiance. After accepting his new guitar, Dechaud and Afric’Ambiance wrested the ceremony from the speakers' grip with a short set that featured “Africa Mokili Mobimba” and “Biantondi Kasanda” with Docteur Nico’s son sitting in on lead guitar.

In length, at least, the career of Leo Sarkisian corresponds closely to Dechaud’s. Born in Massachusetts to parents who escaped the Turkish massacres of Armenians in the 1890s, he developed a love of music and language in surroundings that encouraged exploration of American culture and the Middle Eastern heritage of his parents. A paper he wrote called "World Music," perhaps one of the first coinages of the term, drew Sarkisian from his Greenwich Village studio, where he worked as a commercial artist, to the studios of Radio Recorders in Hollywood. Radio Recorders, one of the main recording companies for the record and film industries, was planning to expand its library of music from around the world, and Sarkisian looked like a promising recruit. In length, at least, the career of Leo Sarkisian corresponds closely to Dechaud’s. Born in Massachusetts to parents who escaped the Turkish massacres of Armenians in the 1890s, he developed a love of music and language in surroundings that encouraged exploration of American culture and the Middle Eastern heritage of his parents. A paper he wrote called "World Music," perhaps one of the first coinages of the term, drew Sarkisian from his Greenwich Village studio, where he worked as a commercial artist, to the studios of Radio Recorders in Hollywood. Radio Recorders, one of the main recording companies for the record and film industries, was planning to expand its library of music from around the world, and Sarkisian looked like a promising recruit.

In 1953, about the time Dechaud was joining African Jazz, Sarkisian shipped out to Pakistan with a vehicle and the best recording equipment he could find. For a year in Pakistan and three more in Afghanistan, he systematically recorded the folk music of different regions of the two countries.

With Ghana's independence in 1957 followed by that of Guinea a year later, Africa became Sarkisian’s next assignment. He worked with renowned musicologist Atta Mensah at Radio Ghana in 1958 and produced an album of local music called New Sounds from a New Nation. In 1959, when Dechaud and African Jazz were playing “Independence Cha Cha” for the participants in the Brussels Round Table Conference on Belgian Congo independence, Sarkisian packed his vehicle and drove north to Guinea. During the next three years he worked with Guinea’s national radio and made field recordings from around the country. As many as 15 albums were eventually produced from his tapes.

Sarkisian joined the Voice of America in 1963 at the urging of Edward R. Murrow, President Kennedy’s director of the U.S. Information Agency. He became the music director of the VOA’s new African programming center in Monrovia, Liberia. A year and a half later, his highly acclaimed program Music Time in Africa made its debut. At first the show featured strictly traditional music from Sarkisian’ s bulging library of field recordings. Even after production moved to Washington, D.C., following the Monrovia center’s closing in 1969, Sarkisian spent as many as eight months a year, up to the mid-eighties, making field recordings in Africa. “This gave me an opportunity to travel to every country on the continent,” he says, except for Zimbabwe and Mozambique, which were off limits to U.S. diplomats until they gained independence. “Ironically, I still get letters now from a radio station or ministry of information from one of these governments saying that, ‘We just heard some traditional music from our country. Where did you get it? We don’t have it, and we would like some.’ And of course I usually try to send the music back to them.”

Today Sarkisian produces two half-hour shows, one for traditional music, the other for pop. Since 1978 Rita Rochelle, who came to VOA from commercial radio and television work in St. Louis, Houston, and Los Angeles, has hosted the program. Together they are better known in Africa than most of the musicians whose works they feature. Passport to World Band Radio, a guide to short wave radio programming, selected Music Time in Africa as one of the 10 best entertainment programs for 1994. Listeners vote with pen and paper showering Sarkisian and Rochelle with some 4-5 thousand letters a month.

Thirty years after “Independence Cha Cha,” external broadcasters like the VOA and BBC have become increasingly important to Africa. The continent’s collapsing economic and political structures have ushered many of its radio stations down the path of destruction. “We are the life line. We are the conduit,” says Rochelle. The importance of music in Africa is enormous, and its loss would be tragic, she says, “I would compare it to trying to exist without oxygen or blood in your system.”

More and more in Africa the blood flows through the speakers of short wave radios. And from time to time through small human gestures like sending a guitar to a musician in Zaire.

Click HERE to view video footage of the presentation.

30 June 1993

It's our last day in Brazzaville. Time to tidy up a few loose ends around town before checking out of our room at the Catholic Mission and saying good-bye to Armand the caretaker. Then we taxi over to the N'soko to stow our bags with Essous until our flight out this evening. Now that the barricades in Bacongo have come down, Essous can get through to the studio again. He has been working night and day to mix the band’s new album, so we haven’t seen much of him lately. Nevertheless, he's waiting for us at the hotel.

Essous accepts our gift and profuse thanks for all he has done. The briefcase is "right on target," he tells us. We mention that we'd like to go out to the Kronenbourg brewery to buy some Ngok' (crocodile, the local beer) stuff as souvenirs. He says he wants to send a letter with us, which he'll write while we go have breakfast. We take our last croissants at the croissant place down the street. The waiter tells us he wants to give us a gift, and we should come back in the evening to collect it.

Out at Kronenbourg we meet Essous's friend, the Directeur Technique M. Léon Quenard. He opens the letter we have brought. It seems Essous has written to him to ask that he help us. "You want some Ngok' items?" he says rhetorically as he sends a guy out to fetch them. Then he takes us out into the brewery to introduce us to the brew master, who gives us a quick and very interesting tour of the brewing and bottling operations. Back at Quenard's office, he presents us with a box of goodies—t-shirts, beer glasses, bottle openers, a couple of trays, and a few yards of Ngok'-print cloth.

We need to bid farewell to Madame Essous and find her at home in the afternoon. We chat awhile and take her photograph. She says she might come visit us one day; since she used to work for Air Afrique she gets a reduced rate on airfare.

Over at the croissant place our waiter friend presents us with a hand-carved miniature table and chair set. He seems like such a sweet guy, and it is a very nice thing for him to do. We exchange addresses and promise to write.

In the evening at the N’Soko we finally get to interview Nino Malapet. He talks for an hour about his career and role in the band. Then we say goodbyes all around and get some rest up in Essous’s room. After a last dinner of rice and sauce in the hotel garden, it’s time to leave. Many thanks and hugs to Essous, and we're off to the airport.

Check-in is unbelievably smooth. No chaos, no bribes. Interview tapes get a reprieve from the X-ray machine thanks to Beth’s eloquent pleas. We are on our way to Paris.

29 June 1993

Back downtown at the U.S. Embassy this morning I find the woman I had been looking for yesterday, the one who could change money. She is a Zimbabwean named Tsitsi, who is buying dollars to pay for a trip home with her son. I get CFA70,000 for $280. That should see us through the rest of the trip.

After breakfast at La Marquise we pick out a nice, black briefcase as our gift for Essous. It's CFA 11,700 but the shop owner knocks off 700 for us. Over at Aujourd'hui we call on Dr. Fylla to see if he can arrange for us to meet Guy-Léon Fylla. Before we leave, we are ushered into the editorial office where the editor and two reporters interview us and take our pictures for publication in the next edition. Then we pile into a cab with a reporter and some other guy for the drive to Guy-Léon Fylla's house in Mongali.

Fylla talks for two very interesting hours about the music’s birth and growth. Now 65, Fylla was something of a mentor to younger musicians coming up in the ‘50s. These days he is better known for his marvelous paintings. Our session is occasionally interrupted by the cries of a mother sheep looking for her kid. In closing, Fylla treats us to a drink while we show him some of the old photos we've collected.

Back at the N'soko we're way late for our rendezvous with Bantous drummer Rikky Siméon. We find Rikky, his wife, and a friend waiting in the garden. Lucky for us, they only arrived a few minutes earlier. We get an hour on tape.

Around 7:00 we call up to Essous's room so that we can take him out for a farewell dinner. When he appears it's obvious he's been sleeping. They worked late last night mixing, then it took a long time to get a ride in from the studio. Once in his room he couldn't sleep, so he made up for it this afternoon.

Dinner at Chez Thiam [see 2 June 1993] isn't much good tonight, and it comes in at over CFA6,300. Still, the guitarist is there as usual, and he and Essous, tears welling in his eyes, do a final chorus of "Essous Spiritou."

28 June 1993

Breakfast in town at La Marquise, then we split up to do chores. Beth goes to Air France to confirm our reservations (they're okay) while I go to the US Embassy to see a contact there about changing money (no luck). We can't change money at the bank either; it seems the woman who does foreign transactions is out. Searching for a thank you gift for Essous, we spot a nice briefcase—CFA 11,500, about $46. Maybe tomorrow if we're able to change money.

We drop in on Dr. Fylla to chat and check out the production of his newspaper, Aujourd'hui. The bi-monthly is put together with top-of-the-line desktop publishing equipment. The whole thing is composed and laid out in the Aujourd'hui offices and then taken to a printer in another location. Dr. Fylla offers to take us to meet the distinguished painter and musician Guy-Léon Fylla. Maybe tomorrow if there's time.

After omelets at Ophelia's near the Plateau Market we taxi over to Pamelo's again, this time to give him a copy of The Beat and the address of a music distributor in Paris that he wanted. He's sitting in the parlor eating rice when we arrive. He accepts the things we have brought and gives us the address of an attorney in Paris, who won a judgment for back royalties from Eddy Gustave on his behalf.

Later, at Pandi's house, I photograph old record jackets and photos from his collection. He also brings out an old publicity brochure from Esengo that includes great photos of many of the studio's stars like Dr. Nico and Kabasele. Pandi presents me with a record album, Les Bantous De La Capitale Bakolo M'Boka, the last with Edo, Pamelo, Kosmos, and three guys, Théo Bitsikou, Samba Mascott, and a drummer called Du Pool, who have all since died.

I tell Pandi I'll try to send him a decent storage box to hold some of the more precious items of his archive. He wants a new pair of glasses too and says he'll send along the prescription. We say our good-byes. He seems genuinely sad to see us go.

At La Centrale for dinner we encounter the usual cacophonous mixture of Brazzavillois, expatriates, hookers, and gaggles of traders, who sell everything from carvings to clothes. It's a non-stop circus, but Essous can't join us for this one. He's still at the studio mixing the new album.

27 June 1993

We still haven't interviewed Nino Malapet, but it's such a nice morning resting in bed. At last we breakfast at La Marquise in centre ville then head over to Nino's to try to make an appointment. He's not home, but a little farther on Pandi is at his house. He shows us some old record jackets he's dug up. We make an appointment for tomorrow afternoon to come back to copy some of his old photos.

At the N'soko Hotel we check for Essous. It turns out he is down at the M'bamou Palace Hotel taping a segment for a television program that he has been working on. After the M'bamou, they'll come back and finish up at the N'soko. We find Nino and some of the other musicians gathering out in the hotel garden.

We have a lunch date just down the road at the home of Madame Essous. We arrive a little early, but she already has everything ready—two kinds of fish, manioc, salad, bread, oranges, plus some wine we bought on the way. Good food and interesting conversation that doesn't lack for gossip. Madame Essous is quite a character. After lunch and a bit more talk, she falls asleep on the sofa. We take the hint and leave.

Back at the N'soko we find that Essous has returned, the day's taping having been completed. All that's left are some voice-overs for the singers, Essous tells us. The show will be on TV in two weeks. Tomorrow the band will be going to the studio to mix the new album. Their "spectacle" has been delayed yet again, however, because of the political turmoil. They'll have to crank up the publicity machine all over again.

We tell Essous about seeing Pamelo and about his feet. Diabetes is nasty he says; both Pamelo's parents died from it. He says one of the presidents—I'm not sure which one—gave Pamelo money to get treatment in Paris, and Essous visited him in the hospital there. He says Pamelo had arrived at the hospital on crutches but could walk without them after receiving medical treatment. Unfortunately, he left before the course of treatment had been completed and used the balance of the money for something else.

26 June 1993

We'll be interviewing Pamelo Mounk'a today, but first Beth and I walk into town to try breakfast at the Black & White Salon de Thé. As we seat ourselves I notice a dead cockroach belly-up on the floor. Another giant one makes a run for the chair next to me. I squish it in mid-course. A few baby roaches scamper along the edge of the table. Not a good first impression. A Congolese man dressed in a modified tux takes our order. He says he is the patron. The croissants are good, coffee not bad, but it's all very expensive, over CFA2000 for the two of us.

After breakfast we check out another bookstore or two then catch a taxi for ONLP. They are open this morning and actually know the book I'm looking for, La Chanson Congolaise, a book ONLP published. A clerk picks up a dusty copy from a display table and hands it to me. Another clerk has a couple copies stuffed in a desk drawer, CFA2000 for another addition to my library. Up the street at Papyrus, Beth uncovers a comic book about Papa Wemba; I buy it for CFA2600. As our time here is running out, we continue on to the artists market to pick up a few souvenirs for friends back home.

At the Centrale for lunch of rice and sauce, Beth notices a large man at the bar playing cozy with a woman who looks very much like a hooker. He's Fylla Saint-Eudes whom we met in Paris [see 4 September 1991]. It turns out he came home a year or so ago and is now editor of a newspaper called Aujourd'hui, using the name Dr. Fylla Di Fua Di Sassa. He says he's working on a short biography of the musician Paul Kamba. He suggests we drop by his office.

After lunch we taxi out toward Pamelo's house. We drop at the new French Cultural center, reasoning that since the soldiers don't seem to check pedestrians we'll walk into Bacongo to avoid being hassled about the camera and tape recorder. But it turns out the soldiers aren't even there today; we took precautions for nothing.

Pamelo is sitting in his parlor chatting with another man when we arrive. We join the conversation, which meanders through current political problems, colonialism, and the splitting of the old kingdom of the Kongo. When the other man leaves, I suggest we go outside to take pictures before we loose the light. Pamelo makes his way to the door with great difficulty. His feet are swollen to at least twice their normal size, and his toes are splayed and disfigured. It’s a symptom of his diabetes, he tells us. He was hospitalized in Paris in the late ‘80s, but they couldn’t do much for him, he says. He is being treated in Brazzaville by a local herbalist. He fears if he returns to Paris for treatment, the doctors will want to amputate his feet.

Pamelo wants to continue in the music business but more on the production side and less as a performer. He remains a pillar of Bantous Monument, a breakaway faction of Les Bantous de la Capitale. But he finds it difficult to operate from Brazzaville, because no reliable distribution system exists to market music outside the country. It’s a complaint we’ve heard many times.

25 June 1993

We hope to see Pamelo Mounk'a today, but first we spend the morning catching up with errands. I change money at the bank while Beth re-registers us with the American embassy. We run into Madame Essous in the street; she invites us for lunch at her house on Sunday. We check out a few bookstores but can't find the Congolese music book Pandi has shown us.

Around 3:00 we walk up toward the Plateau market to check the ONLP bookshop. It's closed. Farther along Papyrus bookshop is closed too. People are selling in the artists market, but everything else is shut down except for a small alimentation shop.

Finally we give up the book hunt and catch a taxi for Pamelo Mounk'a's house in Bacongo. This is an area that was barricaded during the crisis, but it's open now. The only signs of tension remaining are a couple of checkpoints on the main road where soldiers stop and search everyone for weapons. Traffic is considerably backed up while busses and other vehicles are unloaded and people and their bags searched. The soldiers seem to be taking their work seriously instead of merely harassing people for money.

We're in luck this trip; Pamelo is home. We're seated in the parlor as someone knocks on the door of the bedroom to get the big man. A few minutes later he limps slowly out into the parlor. Pamelo is a large, portly, bear of a man who seems robust and healthy except for his limp. He says he got the letter that Essous wrote last time, and he would be pleased to give us an interview. We make an appointment for tomorrow at 3:00.

We decide to walk all the way back to our room at the mission. ONLP still isn't open as we pass. Dreadful dinner at the mission: warmed corned beef from a can, two fish heads, and frozen bread. We'll try to avoid eating here again.

24 June 1993

We leave for Brazzaville today. The Chantilly is closed. We find out today is some sort of holiday, so most businesses are shuttered. It's a holiday left over from some previous regime; no one seems to recall what it's for. Fortunately CAP is serving breakfast—good and much cheaper. Even the coffee tastes good.

Nobody is at Kutula's place when we drop by to bid adieu. We leave letters for him and Roitelet then catch a taxi for the beach. We're in luck; ferries are running today. We pass through an absurd series of checkpoints. First the soldiers guarding the port check our passports. Then people call us over to a side building where they register our passport information. We declare what currency we're carrying, and they collect a "fee" of 2 million zaires each. Next we have to buy a ticket. Both the Congolese and Zairean ferries are running, so we have to figure out which will be first. ONANTRA (Zaire) wins out, and they will take dollars in payment. The cost is 67 million zaires for the two of us. We give them $35.

Roitelet shows up and ushers us through still more formalities. We have to show tickets and passports again. Then we need another slip of paper. That entails going to yet another office to show passports in return for the slip. We have to declare currency again. The official sees our previous declaration, okays that, but says he needs beer money. Good-bye to another 2 million.

Back at the departure gate the mysterious slip of paper gets us through. We show tickets once again then scramble down the ramp onto a large boat that we think is the ferry. But no, a smaller boat just pulling away from the larger boat is the actual ferry. We missed it.

A Congolese ferry comes next, but our tickets are for the Zairean one. We have to wait until it comes back. We strike up a conversation with a man named John, a tall, skinny British missionary who's lived in the bush for 25 years. He's going home for about 3 months but will come back. He has no desire to leave Zaire permanently. He speaks Lingala and even preaches in it. We ride together on the next ONANTRA ferry.

In Brazzaville soldiers stop us on the way out of the port, but otherwise no problem. We don't even go through customs. A little beer money gets rid of the soldiers.

The city appears to be returning to normal. There is gas to fuel taxis again, and shops and government offices are opening up. The barricades came down last night, we are told.

Essous greets us warmly at the Nsoko. He seems genuinely happy to see us. We tell him of our travels in Kinshasa and give him Roitelet's letter. We suggest we should stay at the Catholic Mission (at our expense) this time. He agrees.

Armand, the man who takes care of business at the mission, fixes us up with a room for CFA5,000 ($20) a night. It's about as nice as the Stadium Hostel in Freetown, which costs a mere $2. Anyway it's shelter and the cheapest we can find. There's a big jug of water under the sink; the piped water doesn’t always work. In fact it's not working right now. It'll be a bucket bath on our first night back. Still, it's a relief to have a room and be settled into a nearly normal Brazzaville.

23 June 1993

We plan to return to Brazzaville today. We’re running low on money and remain frightened by the possibilities of more violence as the politicians battle it out on both sides of the river. We haven’t heard anything about conditions in Brazzaville since we left. If things haven’t improved there, closing of the border is still a real possibility.

We breakfast at Chantilly and say good-bye to our room at CAP. We meet Roitelet at Kutula's. Kuktula gives us a bunch of letters to mail for him in the States. He wants to write even more. He looks like he's been working all night. Roitelet tells us he's been listening to radio reports from Brazza; things are still bad there. He wants us to wait another day or two. Also we haven't done our interview with him yet. Beth's ready to go, but she agrees we should stay one more day to at least interview Roitelet.

We reclaim our room at CAP then grab a taxi for Matonge to see if we can catch Verckys by surprise. He left at 7:30 this morning we are told.

Over at the Greek Cultural Center we tell Madame Krissoula of our reception at the Greek embassy. She gives us another name, a Mr. Matamos who can be found down the street in the Shell building. She suggests he might be able to help us.

We figure Matamos must work there, but it turns out to be his apartment—a posh one at that. A servant greets us at the door and shows us into a long, rectangular living room that looks like something out of House Beautiful. At one end there's a grand piano with four chairs sitting in front of it. Leaning against each is an instrument, guitars at two, a viola, and a violin. This guy is into more than Congo Music.

The servant tells us Matamos is in the bathroom. When he finally emerges, he looks like he's just finished his morning shower, even though it's nearly noon. Matamos understands what we want, but he says he lived in the bush in those days (the 1950s and 60s, heyday of Congolese music and the Greek-run recording studios). He takes my card and promises to ask around.

At last we interview Monsieur Roitelet, for nearly three hours. He has lots to tell us of his life and the music business. We agree to meet him tomorrow at Kutula's so he can escort us to the beach for our return to Brazzaville.

Kinshasa has made a big impression on us. This vast city—said to be more than 40 miles from end to end and jammed with ever-increasing millions of people—resembles an animal carcass being picked clean by buzzards. Pillaging and neglect have pushed the city to the edge of collapse. Zaire’s politicians learned well the lessons of their colonial mentors. With a generous assist from Western cold warriors, they appropriated the country’s labor and resources even more boldly than the foreign occupiers. In a just world, the Kissingers and Crockers of America and the Europeans who preceded them would be herded onto a Congo River ferry and dropped off at the Kinshasa wharf to cope on their own with the nightmare they helped create in Central Africa.

22 June 1993

Gerry Dialungana drops by the hostel this morning. He goes along with Beth and me to check out the Greek embassy for leads to Papadimitriou and the other Greek owners of Kinshasa's old recording studios. Inside they tell us they can't give out any information—even if they had it and they don't think they do—because the Greek embassy is only for Greeks.

Over at the Un-Deux-Trois Roitelet is on the way out to try to find Verckys to set up a new appointment, so Gerry takes us on a walking tour of Matonge. We visit a couple of record shops which sell only cassettes now, except for a few used vinyl LPs. Cassettes can be bought for the equivalent of around five or six dollars, but most shops don’t have much of a selection. What they do have comes from Mr. N’Daiye over in Brazzaville. It seems he has the cassette market sewn up. One reason stocks are so low, I suspect, is that dealers have to buy with CFA or another scarce foreign currency, since the zaire is worthless. I buy 3 tapes for 60 million total, about $5 apiece.

Matonge is crowded with lots of shops and little bars, but a goodly number of storefronts stand empty. We are told that this area got hit hard during the pillages, and it appears quite a few were wiped out. We wander through the Rond Point Victoire, a large traffic circle in the center of Matonge, to the famous Vis-à-Vis nightclub. It has gone out of business. The building remains, but it’s empty inside, except for a few piles of sand apparently meant for some future renovation. Gerry tells us the Maison Blanche is out of business too. Suzanella, its owner, died several months ago. Franco’s former manager, Manzenza, and a partner tried to run it for a while but quit, leaving a pile of debts.

Some new clubs, including the Zenith where OK Jazz rehearses, have sprung up to replace the dying veterans, but in general the club scene has declined in direct proportion to the rest of the music business. Only five major bands make their homes in Kinshasa today: OK Jazz, Empire Bakuba, two factions of Zaiko Langa Langa, and Wenge Musica. Zaire’s hottest star, Koffi Olomide, also spends part of his year in Kinshasa. A couple of newer groups, Les As and Equinox, struggle for recognition but haven’t yet built much of a reputation. Studios, too, have declined in number and quality. Verckys still operates his, but most artists seldom record there because he demands too much control. The venerable Studio Star still has only two tracks. OK Jazz crossed the river to lAD in Brazzaville to record their next release.

Back on the Rond Point we pause at a monument to musicians who have died, a statue of uplifted hands rising from a tall, rectangular base around which small plaques containing the names of the honorees should be mounted. But most of the plaques are missing now. They were stolen in the pillaging. The monument itself was controversial because its design was selected without a competition (an arts professor close to power was chosen as designer). Many musicians didn't want to be associated with it.

We are supposed to interview Simaro at 2 o’clock, but he has called a meeting with the band. Gathering outside the Un-Deux-Trois I see Madilu, Josky, Gerry of course, and Flavien among several others I don't readily recognize. Around 5:00 Simaro is ready to see us, up in a parlor off Franco’s old office. He is very courteous and well-spoken, short and to the point. The fifth floor has no electricity, and as the sun sets in the window behind Simaro, he gets harder and harder to see. I have to strain to make out my notes. After an hour the room is pitch black. We decide to call it quits. People light matches in the stairwell as we feel our way down. Finally around the second floor the lights are on. Perhaps the church pays its electric bills but OK Jazz doesn’t.

From the Un-Deux-Trois we follow Roitelet along some back streets to Verckys's place. He has promised to meet us for sure at 7:00. He stands us up again.

21 June 1993

Today’s the day we’re supposed to meet both Wendo and Verckys, but after breakfast at Chantilly I first go back to the Greek Community Center to see Mr. Mimis and Madame Krissoula. After trying several sources, they manage to come up with a telephone number in Athens for Basile Papadimitriou's sister. They suggest I also check at the Greek embassy.

Beth and I had left it that we'd go find Roitelet at his office this morning, but when I return from the Greeks, tireless Roitelet comes to pick us up. He says he went out Sunday (yesterday) and made appointments. We've got an 11 o'clock with Wendo, lunch at 1:30 with his friend Mr. Kutula, and a 4 o'clock with Verckys.

So far there’s no trouble from the soldiers; we wonder if they’ve been paid on time. It’s a rough morning for transportation, however. Fewer and fewer taxis are on the road. Petrol queues go on for blocks. Those who are driving must have connections, or they deal with the Qaddafies. Roitelet, the expert, manages to find a guy who’ll take us to Wendo’s for a reasonably inflated fare.

Wendo is a tall, courtly gentleman with a shiny, bald head. He meets us at the gate of his compound dressed in a crisp, brown suit and wearing a medal around his neck. His yard is covered, it appears on purpose, with broken tile fragments. He ushers us into his parlor where we give him a copy of The Beat and show him the old photos. He seems quite captivated with them as he helps us identify more musicians.

Wendo is one of the more prominent transitional figures in Congo music, one that bridges the gap between traditional and pop styles. As we sit in his parlor, Wendo politely answers my questions then goes outside to pose for pictures.

When we're finished Wendo sends out for drinks and plays us an unmixed portion of a new recording he did for a European filmmaker who has just completed a documentary film about him. The CD is a remake of some of his old songs plus some new ones too. But curiously, Wendo doesn’t play the guitar on it; the producer only wanted him to sing. In fact the version we hear is mostly synthesizer and drum machine. He asks what I think. I don't like the synth, I tell him. He says not to worry. Dizzy Mandjeku and Papa Noel are overdubbing guitar tracks in Brussels. I hope so. But why not let Wendo play his own guitar?

From Wendo's Roitelet gets us a taxi to Kutula's to keep our lunch date. It turns out that Kutula's request for a U.S. visa was turned down this morning. He'd just been to the U.S. in April; it's too soon to go back, the American consul told him. Here's a guy with money, who wants to buy American aircraft and develop trading links, and they won't give him a visa. No wonder there are few American products in Africa. Europeans and Japanese know how to do business and encourage it. Foreigners wanting to trade with the U.S. can't even get past the American embassy.

We pile into Kutula's BMW for the ride to a restaurant near the embassy. It's a fairly fancy place and quite expensive. The owner, an African woman, greets us at the door and ushers us to a table. Everyone who comes in knows Kutula; he often gets up to go to another table to chat. In between he tells us of his interest in the music business and asks us about investors.

Later, while we're eating, Kutula tells a bizarre tale about his new church and the guy who's behind it. According to his story, God dictated nine books to the guy while he, the guy, was under water for three days. Before that the guy had healed a child who was thought to be dead and about to be buried. Oh yeah, and at one point the guy was also set upon by soldiers who tried to kill him, but their bullets and bayonets had no effect. They dropped them and fled. It's a fantastic story, a hodgepodge of stale religious myths whose "good news" Kutula wants to spread. Whoa! Maybe it's a good thing he wasn't issued a visa after all.

From Kutula's office we catch a taxi to Verckys's place, a large, four-story building containing shops and offices in Matonge. Verckys's office sits at one end of the top floor. But Verckys turns out to be as elusive as Wendo is accessible. There’s a lot of muttering and whispering among his staff when we tell them we have a 4 o’clock appointment. They usher us into his office and serve us drinks, but it turns out that, like Elvis, Verckys has left the building.

His office is an impressive space, the walls and ceiling paneled with dark tropical wood. A sultan’s sofa and two matching chairs flank a wooden coffee table at one end of the room. Opposite them a television tuned to CFI, a French overseas service, competes for attention with loudspeakers from across the street. Verckys’s large semicircular desk dominates one end of the office. An overstuffed executive’s chair sits empty behind it, and two smaller versions for guests sit in front. On the wall above the sofa hang two photos of Verckys receiving awards from President Mobutu.

While we wait Franco's old manager, Manzenza, walks in. He is working for Verckys these days. He seems to remember me from our encounter in Washington during the 1989 OK Jazz tour. We talk a bit about that time and the subsequent deaths of band members; he estimates about eleven have died. The subject of Madilu's difficulty getting back in the band also comes up. Manzenza claims that Madilu was the only band member to return to Kinshasa with Franco's body. Roitelet says the others didn't have tickets, but Manzenza says they did.

Eventually he has to go, so we resume our boring wait. We have been told that Verckys was pillaged, but there is no sign of it here. Apparently his recording studio and record pressing factory still operate, and he now publishes two newspapers that are laid out on sophisticated computers just outside his office door. He has also become heavily involved in a new political party. Many irons in the fire and apparently no time for us. We give up after nearly two hours of waiting.

20 June 1993

We go back to the Chantilly for breakfast. An omelet with a basket of bread and croissants and coffee goes for 32 million, about $8. It's expensive but really good. Lots of Europeans and wealthy Zaireans come here. Fancy cars park out front. There are more mobile phones per square foot here than any other place on earth. Zaire's phone system works only sporadically, so to fill the void some enterprising businessmen set up a cellular system to bypass it. Everyone with money has a "telecell," for security if nothing else.

The Chantilly's owner is a Canadian of Pakistani origin. He speaks English and French and is carrying on a family tradition of doing business in Zaire. We ask if he has any ideas about how we can meet some Greek business people in order to trace the old Greeks who owned the early recording studios. He says there's a Greek church and social club not far away on Avenue 30 Juin. Sunday would be a good time for us to find people.

Around 1:00 we leave our room at CAP to go in search of the church. It really is close and beautifully kept up, clean and white with religious paintings on the walls, stained glass windows, and shiny wooden pews. Next door is the social club, containing a bar, restaurant, basketball court with courtside seating, and an exercise room. A number of men (mostly) are sitting around drinking and dining. There aren't more women and children, it turns out, because they've gone to stay in Greece to avoid the dangerous political situation here.

We introduce ourselves to a guy named Nico who introduces us to the manager, a Mr. Mimis. We tell them who we're looking for and ask why so many Greeks ended up here. They seem to think it's a silly question. "They were commerçants. They wanted to make money," they tell us. It's as simple as that. The two of them buy us drinks, then lunch. We're their novelty for the day. They're especially taken with Beth and her excellent French.

Nico and Mimis definitely know of Papadimitriou and Benetar and the others involved in the music business. They think only Papadimitriou is still alive, in Greece. Mr. Mimis says come back tomorrow. Madame Krissoula, a woman who works in the office, will try to help us find more information.

These men, too, warn us that there might be trouble in the city; they think tomorrow, the 21st. The Pakistani guy at Chantilly predicted problems on the 27th or 30th because there is a big political meeting coming up. There are lots of rumors flying around, but clearly nobody really knows much for sure. Meanwhile petrol is getting scarcer and scarcer as gas station owners attempt to drive up prices by refusing to sell. Fewer taxis ply the streets as petrol queues grow longer.

19 June 1993 (Part Two)

Roitelet has told us that Mwanga Paul is still alive, and he wants to take us out to Ndjili to interview him. We catch another dilapidated taxi and drive and drive and drive. Finally we come down at an intersection in Ndjili, but we have to catch another taxi down to Mwanga's street. Roitelet hasn't been out here for ten years, but he manages to find the right place. It's in a fairly well-to-do area with many fancy houses. Mwanga was one of the first to build here.

We leave the taxi and walk a couple hundred yards down the street to find Mwanga in his front yard. A small, rectangular house sits to the rear of the compound; the rest is yard, garden, and chicken coop. Mwanga has been working in the garden. He's dressed only in shorts and is still sweating from his labor. Roitelet introduces us in Lingala as Mwanga sends for chairs and a table so we can sit and talk under a tree. He seems to understand and speak French, but he and Roitelet speak mostly in Lingala.

Understandably, Mwanga seems somewhat annoyed by being dropped in on and pressured into an interview. At Roitelet's urging he appears to relent for the moment. It doesn't seem right, but reluctantly I set up the tape and begin to record. Immediately, Mwanga tells me to stop. He explains that he can't take a photo in the condition he's in, and he doesn't want to do an interview without a photo. He wants to make an appointment for another day. Beth and I are exhausted and not all that crazy to do the interview anyway. We say we'll try again another day. The whole thing is kind of embarrassing for everyone.

We walk back up Mwanga's street to the main road and flag down an old Renault taxi, the kind with the gearshift that slides in and out of the dash. The driver takes us down to the main Ndjili road, following a large truck much too closely. He seems more intent on watching the action alongside the road than he is paying attention to traffic. Suddenly the truck stops, but the driver is looking over at a petrol station to see if they're selling gas. Attention!, we yell. He slams on the brakes; the taxi slides forward into the truck's rear end. Crunch! Traffic begins to move again, and the truck pulls away. Nobody even bothers to get out to look at the damage or make palaver. It's just another battle scar on a taxi that should have retired from the fight years ago.

On the main thoroughfare we flag down another taxi for the trip into town. This is the worst yet. The engine deposits its exhaust directly into the passenger compartment, which is blue with acrid smoke. And we have a long way to go. The driver takes the industrial road along the river, past the docks and the Kinshasa-Matadi railroad. Along the road a kid jumps in front of the taxi. The driver jams on his brakes, and the kid jumps back just in time. He scares us badly. With our heads hanging out the window for fresh air, we chug on into the city past the "beach" and the American embassy.

We haven't eaten all day, so we walk up to the corner near our hostel to try the Chantilly, an ice cream parlor, bakery, and sandwich shop that seems so out of place here. Anyhow, it's great. I have a ham and cheese on delicious French bread.

19 June 1993 (Part One)

We’ve spent our last night in Kintambo and this morning pack for our move to the hostel downtown. A priest who’s going into town agrees to take us along. On the way, we meet a huge petrol queue outside a Mobil station. We’ve been seeing these at every gas station for the last two days. The station owners want to raise prices, but Mobutu’s government won’t let them, so they ration gas or simply refuse to sell altogether. The priest needs gas. He pulls off to one side of the queue in front of a soldier who’s surveying the chaotic scene before him. Our car is immediately besieged by guys with plastic containers of gas. They call them “Qaddafies” here. They sell petrol when the stations don’t. The cost: 15 million zaires (about $3.40) for five liters, well above the regulation price. It’s the parallel market in action right under the nose of the law who couldn’t care less. The priest buys from a young kid, then we gently work our way through the throngs waiting for transportation and out into traffic. Farther along we meet more people waiting for a ride. The priest stops and picks up two elderly white women. Nuns I suspect.

Roitelet meets us at the CAP hostel. We check in, unpack, and ready a bag for the day's work. We walk over to the offices of Roitelet's businessman friend, a Mr. Kutula, who has headquarters at the rear of a nearby mini-mall on Avenue 30 Juin. One of Kutula's lieutenants speaks good English. We chat a bit, the lieutenant explaining that he and Kutula are going to the U.S. next month to look for used aircraft in Texas. Kutula changes money for us, 4.4 million zaires for 1 dollar. Meanwhile Roitelet has reached Roger Izeidi using Kutula's phone. Roger says come on out to his place.

We wander along Avenue 30 Juin in search of transportation. Many of Kinshasa's taxis ply a fixed route disgorging and picking up passengers like a bus. Others call themselves “taxi express” and for a price will take you anywhere you want to go. We have been told to be very cautious about taxis and not to board one with male passengers. The unwary are often kidnapped by groups of men, driven to an out-of-the-way spot, and relieved of all their valuables.

We catch an express out to Limete near Franco’s house and turn off the main road, to the left this time. Down a paved side street past warehouses and various other commercial concerns, we get out near yet another walled compound. Inside the gate a large, very comfortable looking house sits on the right. On the left there’s a long low building sectioned off and rented out to small businesses. Behind that is the office of Roger Izeidi. Roger, a veteran of Kabasele’s African Jazz and a longtime producer, is quite recognizable although he’s now 30 years older than the pictures I’ve seen. He is a short man, still slim and spry, and as full of energy as I’d imagined. He still works in the music business although he has left the pop side to produce traditional groups.

Roger invites us to sit under a tree on the lawn of the big house, which turns out to be his. He sends out for drinks while we look over the old photos I've brought. He’s amazed to hear that Bill Alexandre is still alive. "Ah, Bill. He' our father," he and Roitelet exclaim over and over. Both help us identify more people in the photos, then we do the interview. Very informative—in contrast to Dechaud—it ties up lots of loose ends.

Afterward Roger invites me inside. His whole compound was looted by rampaging soldiers during one of the pillages. The TV, phone, some fixtures, all were stolen. Roger was shot in the foot and needed surgery to repair the damage.

Roger points out that MAZADIS is next door and asks if we'd like to see it. Of course. MAZADIS signs, the paint flaking badly, still adorn the walls on either side of the main gate. This is the studio and pressing plant that Willy Pelgrims built in the late ‘50s, where many classic Congo music recordings were made. The building is constructed in three sections, maybe 30 feet high, 30 feet wide, and as long as half a football field. The left hand section contains offices and the mastering equipment; the middle houses the studio and other miscellaneous offices. The right hand section contains the manufacturing equipment, including hand-operated record pressing machines for 45 and 33 r.p.m. discs. Following Zaireanization of foreign-owned businesses in 1973, the government turned the whole complex over to Franco. Now it sits idle. During the week someone comes in to open the doors. Today only a watchman looks on. Franco’s old equipment truck sits forlornly off to one side. The tires are flat; it isn’t used any more.

18 June 1993

A search for Roitelet and Dechaud is on our docket for today. Beth was recuperating yesterday, so we stayed in our tranquil Kintambo compound. She started eating again and generally feeling better, so today we decide to venture downtown. On the way we see a guy selling newspapers. The headline on one says that Qaddafi has retaliated against Congo for killing his ambassador by killing the Congolese ambassador in Tripoli (this, like much of what appears in the Zairean press, later proves to be untrue).

Over at the U.S. embassy we meet with Donna Anderson, the consul. Just as we are gaining confidence that things are normal and we’ll be okay, she tells us terrifying stories about the second pillage that happened this past January. A lot of killing took place in the square across the street from her office two blocks away from the main embassy building. She says she narrowly escaped being shot as she fled the scene in her car. A guy pointed a gun at her, but she ducked and tromped on the accelerator. He didn't fire. She doesn’t think we should even be in Zaire, but especially not in Kintambo. There’s lots of crime there, she tells us—robbery, car hijackings, and the like. Soldiers are supposed to be paid on the 20th, she adds for good measure. That’s two days from now. When they don’t get paid, they get nasty.

We ride with Ms. Anderson to her office where we officially register our presence in case of emergency. A Zairean named Andrew, who has retired after 30 years working for the embassy, helps us find a taxi to go in search of Roitelet. He haggles with a driver for a fare of 8,000,000 zaires. The two of them seem agreed as to where Roitelet lives. Some distance away, on Rue Kitega in a poor area of Kin, we decide to proceed on foot. Andrew and the driver tell us the address is farther down toward Avenue Kasavubu. They were right. We find we must walk through several blocks of sewage-soaked, garbage-strewn back streets. Housing here is similar to that of other African cities I've visited, but clearly sanitation services no longer function. Nevertheless, everyone we encounter seems friendly, and several warmly greet us.

Finally, near the corner of Kitega and Kasavubu, we find number 118, Roitelet's family compound. He has moved back to his parents' place after his own house was ransacked in January. He's not at home his daughter tells us. She says he has two offices, one at Soneca downtown and one at the Un-Deux-Trois, Franco's old club. He's at the Un-Deux-Trois today, so for another 8m zaires we taxi over there.

The Un-Deux-Trois is a mess. With its faded paint and broken windows, it looks abandoned. Inside, the main club is still intact, a combination indoor/outdoor configuration. The structure's four or five stories are built around an open-air courtyard. A covered pavilion with benches to seat maybe 200 people sits in the center of the courtyard facing a stage attached to one side of the building (presumably this was once the main club's dance floor). Additional seats on the first floor of the tallest portion of the building look out at the courtyard and stage. Second floor balconies offer a similar view of the action.

These days the club no longer functions. Instead, it’s being rented for use as an evangelic church (thus the benches on the dance floor). A preacher’s pulpit and a five-piece band playing religious music sit on the stage where Franco once performed. The pavilion and stage seem to be in good shape, but the farther we wander, the worse the condition. Bathrooms don't work, and there's a goat tethered in an outer entryway. Some fixtures are missing and wiring disconnected or pulled out of the wall. The auxiliary bars upstairs that once offered high rollers a more intimate space in which to carouse, are completely abandoned. OK Jazz has to rehearse at the Zenith, a new club down the street. Upper floors of one wing of the building still house the band’s offices, however, along with one for the musicians’ union (UMUZA).

Upstairs we find the band's secretary typing something on OK Jazz letterhead. He says Roitelet isn't around, but Simaro is. We climb another flight or two to the top floor and walk through a dim anteroom into a nicely furnished parlor with carpet on the floor and comfortable chairs. Simaro is sitting there chatting with a woman when we walk in. He rises to greet us as we introduce ourselves. He agrees to an interview next Tuesday.

After a short wait in the UMUZA office, Roitelet comes up the stairs. We give him Essous’s letters and tell him what we’re up to. With great interest he examines some of the old photos we've brought. He's amazed to learn that Bill Alexandre is still alive. We ask about security in town and the soldiers' impending payday. He agrees that we should move out of Kintambo but says we needn’t worry about the soldiers. He doesn’t think there will be any trouble. Gerry Dialungana, a guitarist I met when OK Jazz came to the U.S., wanders in. He’s very surprised to see me again. He agrees with Roitelet that we should move, so it’s decided that we will go to a Protestant hostel—known locally as CAP—near the center of town to arrange for lodging.

On the way downstairs, we meet Madilu System, le grand ninja of OK Jazz, coming up. Outside we see Simaro again, leaning up against his Mercedes. We walk down the street toward the Zenith where Gerry gives us a brief tour. The club is basically three walls with a roof that covers a seating area. The walls extend beyond the roof to enclose an open area for dancing. Beyond that, against a fourth wall, another covered area serves as stage for the performers. A bar stretches out along the left wall under the seating area's roof. Gerry calls Flavien over to say hello. He's the bass player who came to Washington with the band.

Back outside we continue along in search of an empty taxi. "The transportation situation is difficult," says Roitelet. "They steal cars in Zaire and sell them in Angola. They steal cars in Zambia and sell them in Zaire." Those that run in Kinshasa are in very poor condition. The state of the economy makes it harder and harder to get spare parts. Two out of every three cars belch acrid smoke as they sputter about the city. Our eyes burn as if we were in Los Angeles or Mexico City. Almost anywhere else most of these vehicles would be in a junkyard.

Gerry calls out, “Josky!” We look over, and sure enough there’s Josky Kiambukuta leaning against a wall talking to someone. “Here,” says Roitelet, “we don’t separate ourselves from the public like they do in America. We like to be with the people.” The musicians, he says, “see what’s going on in people’s lives and put it into the songs."

Eventually we find a taxi to take us to CAP. The four of us pile into yet another vehicle with no suspension. The impact of every bump—potholes are rampant—reverberates directly to the tail bone. The driver is a nice guy who gets us safely to the hostel. He waits while we register. According to the home church in Kentucky (we contacted them before we left the States) this place is closed, yet here we are, and it's open for business. The woman at the desk says it'll cost $15 per night. We tell her we're Presbyterians. That's different she says, it's half price for us. She shows us a room. The toilet has an actual toilet seat. I'm sold right there. We tell her we'll take it starting tomorrow.

Once we secure lodging, we taxi out to Limite, an industrial area of Kinshasa where many of the city’s wealthy live. During colonial times this was home for Europeans. The taxi leaves the main road and gently rolls down an increasingly narrow and rocky street. On the right sits Franco’s house, a walled compound containing what appears to be three, two-story buildings—a large center house flanked by two smaller ones. If not architecturally remarkable, it’s at least ostentatious enough for a great star like Franco.

Finally the road is too bad for the taxi to continue. We get out and walk down the rocky lane toward the former home of Docteur Nico. Beth looks at me and exclaims, “Where’s your bag?” My heart jumps. I turn and yell at the taxi that’s starting back up the road. The driver hears and stops. I’d put my bag with my tape recorder, camera, money, everything in his trunk and in my state of euphoria had forgotten all about it. A few more seconds and my entire trip would have gone down the drain. The driver realizes why we yelled. He apologizes and says he would have come back for us when he discovered what had happened. Whew!

Down at the end of the lane, we come to Nico’s walled compound—walls are big here. Inside sits a well-kept main house that Nico’s children, we are told, now rent out. Behind the house is a large grassy area overgrown with weeds. “This is where his body was laid out for viewing,” Roitelet tells us. Beyond, in the rear corner of the compound, sits a small two-room house. Here Nico’s brother and collaborator, Mwamba Dechaud, the great guitar accompanist, now spends his last days. Thin and frail, Dechaud rarely goes out any more. Roitelet calls out greetings and ushers us in to meet a 60-year-old man who looks more like 80.

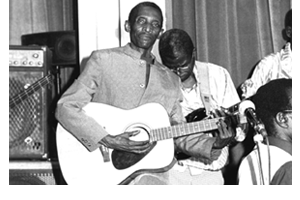

Dechaud's small parlor is dimly lit by two open windows and the cloth-draped door opening. Dechaud gets up from the chair where he’s been sitting with his ear cocked against a large radio-tape player. Old records and photos of Nico and their mother hang on the wall opposite the door. On the wall next to the bedroom door hand-painted, black letters proclaim, "Mwamba Mongala qui à l'epoque a fait danser Lucifer et ses 500.000 diables" (Mwamba Mongala who in the old days made Lucifer and his 500,000 devils dance).

Dechaud seems to understand French but prefers to speak Lingala, so Roitelet translates. Dechaud doesn’t talk very much. Often he’ll answer with a simple yes or no; some things he won't even talk about. Roitelet often ends up interjecting his own answers to questions I've posed. It doesn’t make for a very satisfactory interview, but it is an incredible experience just meeting the man. Dechaud doesn’t even have a guitar to play any more. He asks if we can send one from the States. I tell him I’ll try my best. He puts on a suit jacket to pose for photos, then it’s time to leave. He walks us to the compound gate. “Don’t forget the guitar,” he says earnestly with a piercing, almost desperate look in his eyes. I assure him I won’t.

16 June 1993

Beth is sick this morning. Maybe it was last night’s food (never eat raw vegetables in the tropics unless you wash them yourself), maybe the tension. By 8:00 a.m. she's feeling a little better, so we decide to try it. Out in the city it’s still a quasi ville morte. Apparently trains still can't get to Brazza, so there's no gas at the petrol stations. Heading for the beach down Avenue de la Paix, our taxi weaves through remnants of barricades that had been thrown up to block traffic. The barricades plus some burned spots on the road and a couple of stripped vehicles suggest there was trouble here last night. Closer to the center of town we begin to see armed soldiers at street intersections. We get stopped and searched at the junction where gunfire scared us half to death yesterday.

It looks like things are happening at the beach. Lots of travelers gather around lots of luggage. ONATRA, the Zairean maritime company, is open and selling one-way ferry tickets for CFA6,500. As I leave the ticket window, the official we got information from yesterday comes up and re-introduces himself. He takes our passports and leads us past the guard who's supposed to check them and through the gate to the ferry landing. "Do they have bombs?" asks the guard as we pass by. "Les grands terroristes," smirks our man. He does whatever he does in his office with our passports then takes us to the mobbed immigration window. "Wait," he says and goes into the office avoiding the clamor at the window. A few minutes later he emerges, hands us our passports, and says everything's okay. We thank him profusely for saving us all the bureaucratic hoops. I shake his hand and slip him a CFA1,000 note. (Later it dawns on me that this easy passage may have been the work of Essous. He seems to have connections everywhere.)

Beth is really feeling horrible. She lies down on a large heavy-equipment tire in an effort to appease her stomach. A white woman with a small baby and a U.S. Embassy I.D. badge walks over. She's Dr. Julia Weeks of the Zaire-American Clinic in Kintambo (a district of Kinshasa). She tells us to come to the clinic if Beth doesn't begin to feel better.

Around 10:30 or so we see the ferry steaming toward us from Kinshasa. It’s really two ferries bound together somehow. Why?, we wonder. It’s hard to tell. The ferry nestles up to the dock and disgorges its cargo. Our queue begins to inch forward. The little shelter with curtained openings marked hommes and femmes that I thought housed toilets for our traveling convenience turns out to be yet another hurdle between us and the ferry. Apparently we are to be individually questioned and searched. The line inches forward, the women moving much faster than the men. Beth disappears inside, but I'm a dozen or so men away from the door. Suddenly our savior from previous formalities appears. He takes our passports and tickets, flashes them appropriately as we slalom through the remaining officials, and leads us into an air-conditioned cabin on board the ferry where Beth can lie down. More thank-yous and we promise to come see him when we get back. Right now I’ve got to save some bribe money for the other side.

While we wait for departure, an American guy we met in line comes in to see how Beth is doing. He's a pilot with an aviation service run by missionaries in Zaire. The border is currently closed to light aircraft, and, since he lives in Brazza and flies in Zaire, he and his family are forced to commute by ferry. After some minutes, a loud cheer from outside interrupts our conversation as a small motorboat speeds away in the direction of Kinshasa. We are told that it carries Monseigneur Laurent Mosengwo, chairman of the High Council of the Republic, a parallel government formed in opposition to Zaire’s president Mobutu.

Finally the ferry sounds a couple of blasts on its horn and slowly slips away from the dock. Clumps of green vegetation float past as we chug along on our 20-minute crossing. From time to time a large white bird surfs by on one of these grassy vessels. What a life! A man comes into the cabin carrying a five- or six-month-old baby girl. I slide over to make room for him to sit down. Soon he gets up, plops the baby down beside me, and leaves the cabin. Moments later, a young woman, the baby's mother, comes in and sits with the little girl. She's a Zairean traveling home from Montreal to introduce her new daughter to the rest of the family. She and Beth have a good conversation in French. The woman says to wait for her when the ferry reaches Kinshasa so we can all disembark together. She says she has people meeting her at the landing.

It’s bedlam as we dock at the Kinshasa wharf. Passengers struggle up the ramp with their bags while blue-suited cargo handlers race down into their midst trying to get first crack at the ferry’s cache of bags and cartons. We follow the man and woman with the baby. They have promised to help us navigate the formalities. True to their word, they adroitly maneuver us through with only a minimum of hassle. One official gestures to us as if to say “buy us some beer.” I give him CFA1,000 and tell him to split it with his two co-workers. That seems to be satisfactory.

Outside we meet a taxi driver named Willy who, for 30 million zaires, will take us to a seminary near Matonge, the heart of Kinshasa’s night life, where we are told we can find cheap lodging. The zaire, Zaire’s currency, is on a headlong free fall that must be unparalleled in modern times. One dollar, which couldn’t purchase one zaire when the money was first issued back in the ‘60s, now buys 4,400,000 of them. Willy’s 30-million-zaire taxi ride is costing us about seven bucks.

As we drive along we see many abandoned shops, perhaps victims of one or another "pillage." Events here are now marked by their relationship to the "premier pillage" or the "deuxième pillage," or some other catastrophe that has occurred in the last three years. But despite its incredible problems the city still seems to function, as much from necessity as design. There are even cops out directing traffic.

Unfortunately the seminary can’t house us. The rector directs us to the Mission Catholique Nganda in the Kintambo district. It’s quite a distance from the center of town and will make getting around more difficult. But they have rooms and food at affordable prices in a clean, tranquil setting. It's perfect for us. Who needs the Intercontinental?

15 June 1993

We're not quite as tense as we were yesterday. We go off to the patisserie, but it's closed today. Petit dejeuner consists of bread and cheese from a small shop that dares to open across the street. We are edging closer to deciding to go to Kinshasa, despite the horror stories. We share a taxi into town to make one final assessment of the situation. For the first time we see armed soldiers at major intersections along the way.

We stop first at Air France. The office is open today and has lots of customers. Apparently a number of people are getting out of town because of the political crisis. I leave Beth to deal with our reservations and head over to the US embassy to try to talk to Cedric, the doctor who knows about the ferry. After a few minutes he comes down to the lobby to see what I want. He seems nervous and distracted. We had tried to phone him earlier and were told he'd gone over to the Swiss Air office. Maybe he's trying to get his family out of the country. He tells me that the Congolese ferry isn't running now because of the trouble. He doesn't know about the Zairean one. Go to the beach (local shorthand for the ferry terminal) to find out for sure, he suggests. He doesn't seem to want to talk much, and when he says good-bye he heads out the door and across the street instead of returning to his office. I imagine him going back to Swiss Air.

At Air France I find Beth just getting her turn at the counter. The attendant tells us there's no problem changing reservations as long as there are seats available. Our tickets are good until September. Great! We can stay for Essous's "spectacle" if it happens.

At this point we've pretty much decided to go to Kinshasa, if we can get a ferry; we go to the dock to check. Along the way we pass the treasury and the round office building, Tour Nabemba (also known as Elf Tower, for the French petroleum company), something of a skyscraper at more than 300 feet. Both are closed, presumably due to the troubles. Farther on we pass the posh Hotel Cosmos and the Russian Embassy, what looks to be an old colonial era building set back from the road behind a park-like expanse of lush lawn and tree-lined driveway.

Down at the junction leading to the "beach" armed soldiers search cars and harass pedestrians. One of them sits in a chair on the corner getting his shoes shined. We make the mistake of asking him if this is the correct road to the ferry terminal. He jumps up and demands to know where we're going. He wants to see passports and search our bags. Eventually he lets us pass, and we go on down to the terminal. An official there tells us the Zairean ferry is still operating. He assures us we can cross tomorrow if we want to.

We head back toward the town center, but as we approach the soldiers at the junction shots ring out. Everybody scatters. We scramble up an embankment and hug the ground behind some bushes near a wall. Cars squeal past us in reverse as the firing of automatic rifles continues. We can’t see what’s happening, but gather they’re firing in the air to scare someone. They have succeeded with us.

After several tense moments, cars begin to edge forward again, and people begin to pick themselves up off the ground. It’s not clear what happened, but nobody bothers us as we walk away. The same soldier is still sitting in a chair getting his shoes shined.

After coffee and a rest we walk up to the Catholic Mission to keep our appointment with David's Zairean friend, Abbot Claude Ngoma. We're about an hour late, but Claude is there to greet us. We're on African time, we tell him. Claude is very cordial. He tells us he's already sent a letter on our behalf to the seminary in Matonge (a district of Kinshasa) where he works. He gives us other letters to take with us, along with directions for how to find the place. He assures us we can stay there and probably use the seminary's car and driver too. His assurances pretty much seal our decision to go.

Upstairs we chat with David for a few minutes. He shows us a laptop computer that he uses in his work. It's an unusual sight in these parts. Beth borrows a book to read in Kin, then the three of us walk up to the Villa Washington, a club for Embassy and Peace Corps staff, to get something to eat and perhaps go for a swim. They have hamburgers and pizza and French fries on the menu. We run into James Kuklinski, the Peace Corps director. He tells us that they are evacuating volunteers to a third country, perhaps Cameroon or Kenya. Word has already gone out to them to leave their posts and gather at pickup points. He says the embassy is close to a decision to evacuate non-essential personnel and dependents. It seems the situation in Congo is worse than we thought. David wonders what to do. He can't carry out his AIDS research under these conditions. A Peace Corps volunteer suggests he fly to Pointe Noire to wait out the crisis. Things are better there, she says, and they have an airport so one can fly out to Gabon or Cameroon if things get really bad.

Back at the hotel Essous agrees that we should try to make the crossing tomorrow. He assures us we'll be okay; we just have to remember to pay small bribes along the way. Last week he sent an emissary to Roitelet in an effort to smooth the way for us. Now he gets busy writing other letters for us to carry along to help make introductions. He'll keep our suitcases in his room for us until we get back. We plan to travel light to Kinshasa.

After packing, we eat our last dinner of sardines and bread over placemats made of pages torn from an Air Afrique in-flight magazine. A white fashion model peers from behind the black pleated collar of an absurd Paris fashion creation to tout Ystais perfume from Givenchy. A go-getter type in crisp business suit boards a welcoming van for the ride to his $150-a-night room at the Novotel. He’s a jeune cadre dynamique (in essence, a yuppie).Maybe I’ll use that line on Zairean immigration authorities tomorrow. Occupation? Jeune cadre dynamique.

14 June 1993

Things don't appear to be back to normal, but at least the neighborhood patisserie has opened up. It's a mob scene in front of the counter as customers clamor for service while a beleaguered, substitute counter attendant (the regular apparently couldn't make it in) tries to contend with complex orders and a shortage of change. The unflappable waiter is his usual steady self, however, so those of us sitting at tables get the good service to which we've become accustomed.

Outside there aren't many taxis running. We hear that there isn't any more petrol in town. Word is the train tracks have been sabotaged in some manner, so supplies from the refinery at Pointe Noire and food from the port there can't get to Brazzaville. We meet another couple looking for a taxi to centre ville, and when one finally comes along we share. The fare is up to CFA1,000 now, double the normal cost. Downtown looks like a quasi ville morte; many businesses and most offices are closed. At the American Embassy, the counselor tells us that Kinshasa is much more dangerous than Brazzaville because of crime, but politically Kin is calmer at the moment. She feels the political tension in Brazza is getting worse, and she's not sure how it will play out. U.S. authorities are considering evacuating non-essential embassy personnel and Peace Corps volunteers from Congo in the coming days.

As for Kinshasa, the Intercontinental is the only place she can really recommend for security, "anywhere else you are taking a risk." At $160 a night we'll blow our budget for the entire trip across the river in four nights. Her advice about the ferry and customs: just go there and try your luck. Cedric, the embassy doctor, goes every Wednesday on the 8:00 a.m. boat, but she doesn't offer to let us talk to him. "Take the 8:00 a.m. boat," she says, "you can talk to him during the crossing."

From the embassy we cross the street and walk down to the office of Air France to see how difficult it will be to change our reservations if we have to. The place is locked; apparently people were afraid to come to work. We also wanted to check for a book on Congo music that Pandi showed us, but no bookstores are open either.

Back at the hotel, the tension and uncertainty start to get to us. Kinshasa stories are scary enough, but now Brazzaville seems to be falling apart too. What if we go to Kinshasa and then Congo closes the border? How will we get home? Maybe we should just pack it in and go home now. But we're so close to all the musicians I've wanted to meet, I feel I've got to at least try to see them. I offer Beth the option of going back to Paris, but she says she doesn't want to leave me here. For now, we put off making any decisions.

13 June 1993

There is some activity in the streets, so it looks like it’s safe to go out. Nino Malapet is supposed to come for an interview this morning. Outside, our favorite corner shop is closed. Down on the main road the patisserie is closed too. One of the shops run by Mauritanian merchants has opened, however, so we buy some cheese and a jar of strawberry jam for our petit dejeuner.

Morning wears into afternoon and Nino still hasn't shown up. Essous thinks he's probably afraid to go out. We call a new acquaintance, David Eaton, a Ph.D. candidate from Berkeley who's here doing AIDs research, and he agrees to come pay us a visit. We sit around the N'Soko Hotel garden sipping drinks and talking music, AIDs, and politics. We're all getting hungry, so we decide to go to the restaurant at Club Washington, an American enclave near the Peace Corps office. The kitchen is closed; the cook couldn't get to work because of the current situation.

Now we're really hungry, so we press on into the center of the deserted city in hopes of finding an open café (along the way we pass several roads barricaded with tree limbs and boards). Le Centrale doesn't let us down. This Lebanese-run bar and its competitor across the street are the only things going. Few people are out; there are only three tables occupied in the whole place. Two Lebanese women who appear to run the place are sitting outside with the customers. We ask if they can make us food. They say omelets and fries are about it, no rice or other more complicated stuff. We each have an omelet, sodas, and share a plate of fries. Total: CFA6,100, about $24. This place is expensive!

After eating we walk to the Catholic Mission near Peace Corps where David is staying to look for a Zairean guy who might be able to update us about Kinshasa. He's not in, so we catch a taxi back to the hotel, saying goodbye to David. In parting he gives me a couple of newspapers with articles about Guy-Leon Fylla and Franklin Boukaka. He knows a lot of Zairean music, having lived in Zaire for a while. He was evacuated during the premier pillage.